Sony Design

Key Person Interview

December 2006

http://www.sony.net/Fun/design/activity/interview/mogi_01.html/

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Aha! experience on Play Station Portable.

This year, I helped Sega create two games on Sony Play Station Portable based on the phenomenon of change blindness. Here's a few of the reviews (in English) of the game.

http://www.gamesetwatch.com/2006/06/aha_taiken_spots_the_differenc.php

http://psp.ign.com/objects/820/820930.html

On the game packages and the press releases, my name is spelt as "Kenichiro Mogi". That is my formal name. Ken is an abbreviation. All my friends call me Ken.

One of the reasons why I helped develop this particular game was because I wanted to promote public awareness of what a creative organ the brain is. There is too much emphasis on drilling the brain to do arithmetic etc., in which function the computer is far better anyway. I would like people from all walks of life to realize the potentials inherent in themselves.

Here's my earlier essay on the significance of the Aha! experience.

Onceness and the philosopher's walk

(Now available as a chapter in "The Future of Learning")

"The game package"

http://www.gamesetwatch.com/2006/06/aha_taiken_spots_the_differenc.php

http://psp.ign.com/objects/820/820930.html

On the game packages and the press releases, my name is spelt as "Kenichiro Mogi". That is my formal name. Ken is an abbreviation. All my friends call me Ken.

One of the reasons why I helped develop this particular game was because I wanted to promote public awareness of what a creative organ the brain is. There is too much emphasis on drilling the brain to do arithmetic etc., in which function the computer is far better anyway. I would like people from all walks of life to realize the potentials inherent in themselves.

Here's my earlier essay on the significance of the Aha! experience.

Onceness and the philosopher's walk

(Now available as a chapter in "The Future of Learning")

"The game package"

Beyond this linguistic closure

Some time ago, aneta made a comment on my earlier entry and asked how I divided the topics between my English and Japanese blogs.

My blog in Japanese has been running for 7 years now, starting on the 12th of November, 2006. It is fairly well established in its style and readership. The entries during the period of 2004 to 2005 has been edited into a book (Yawaraka-nou, or "The flexible brain"), published from Tokuma-shoten.

My English blog, on the other hand, is far from being established and is in the process of experimentation.

Actually, expressing oneself in English, while living in Tokyo and being absorbed more or less in the Japanese cultural environment, is a difficult task. It is related to the context in which the Japanese people and culture are thrown into in the modern age.

Since the Meiji revolution, Japan has been playing the game of a catch up. It has been customary for the intellectuals to "import" ideas developed in Europe and the States, and the same process is basically happening even today. I am not saying that no original ideas have been nurtured in this country. I am just pointing out that the product of Japanese intellectuals have failed to find its market outside Japan. Although Japanese sub-culture (Manga, Anime, Otaku) are getting popular in the world market, many intellectuals (university professors etc.) in Japan remain in a "domestic" existence.

Japan as a nation has a tendency to be closed and self-contained, mainly because of the language. Once you write something in Japanese, it is almost certain that the majority of the readership will be Japanese citizens. I have published ~20 books in Japanese, and I well know that my readership will be effectively limited to this island country as long as I keep publishing in my native tongue.

I think this linguistic closure is bad for me personally and for people in general living in Japan. There is a nationalistic trend rampant recently, and I am personally worried. A sense of universal liberty and a tolerance towards people from different backgrounds can only come from an effort to meet the unknown, to communicate, however clumsily, with people who literally speak a different language.

My English blog is in a totally different context from the Japanese blog, and I enjoy the contextual departure. When I write something in English, my imagined readership is not necessarily people from countries where the native tongue is English. Although I do much appreciate people from U.K., the United States, Canada, Australia, to read my blog, I would at the same time very much like people from regions of minority languages, whose only means of opening oneself to the wider world is by adapting to the English language, to access my humble blog.

I do not know where this experimentation is leading me. I will keep writing any way.

My blog in Japanese has been running for 7 years now, starting on the 12th of November, 2006. It is fairly well established in its style and readership. The entries during the period of 2004 to 2005 has been edited into a book (Yawaraka-nou, or "The flexible brain"), published from Tokuma-shoten.

My English blog, on the other hand, is far from being established and is in the process of experimentation.

Actually, expressing oneself in English, while living in Tokyo and being absorbed more or less in the Japanese cultural environment, is a difficult task. It is related to the context in which the Japanese people and culture are thrown into in the modern age.

Since the Meiji revolution, Japan has been playing the game of a catch up. It has been customary for the intellectuals to "import" ideas developed in Europe and the States, and the same process is basically happening even today. I am not saying that no original ideas have been nurtured in this country. I am just pointing out that the product of Japanese intellectuals have failed to find its market outside Japan. Although Japanese sub-culture (Manga, Anime, Otaku) are getting popular in the world market, many intellectuals (university professors etc.) in Japan remain in a "domestic" existence.

Japan as a nation has a tendency to be closed and self-contained, mainly because of the language. Once you write something in Japanese, it is almost certain that the majority of the readership will be Japanese citizens. I have published ~20 books in Japanese, and I well know that my readership will be effectively limited to this island country as long as I keep publishing in my native tongue.

I think this linguistic closure is bad for me personally and for people in general living in Japan. There is a nationalistic trend rampant recently, and I am personally worried. A sense of universal liberty and a tolerance towards people from different backgrounds can only come from an effort to meet the unknown, to communicate, however clumsily, with people who literally speak a different language.

My English blog is in a totally different context from the Japanese blog, and I enjoy the contextual departure. When I write something in English, my imagined readership is not necessarily people from countries where the native tongue is English. Although I do much appreciate people from U.K., the United States, Canada, Australia, to read my blog, I would at the same time very much like people from regions of minority languages, whose only means of opening oneself to the wider world is by adapting to the English language, to access my humble blog.

I do not know where this experimentation is leading me. I will keep writing any way.

Friday, December 29, 2006

Idiot Train

There are some books that I read again and again. Hyakken Uchida (1889-1971)'s "Idiot Train" (Aho Ressha) is one of my all time favorites. It is a humorous writing on Uchida's own beloved past-time, riding on the train for pleasure. In the Idiot Train essay series, he goes all over Japan trying to satisfy somehow his insatiable desire for train rides. It is no ordinary travel essay, though. Uchida does not want any of that distraction or enlightenment people normally expect from getting to see things in a new land. He just wants to travel on the train, drinking sake and having an interesting conversation, and that's that.

In the opening sentence of the first volume of the Idiot Train, Uchida confesses thus (translation from Japanese mine)

I call this trip idiot train because people would say so behind my back anyway. Needless to say, I myself do not consider this undertaking to be that of an idiot. To be honest, you don't need a reason to go somewhere. I don't have any reason in particular to do so, but I have made up my mind to go to Osaka on the train.

As I do not have any particular reason to make this trip, it is ridiculous to travel second or third class. Traveling first class is always the best. At the age of 50, I made up my mind to always travel first class. In spite of my determination, I might be obliged to travel third class when I have no money and yet have some specific reason to make the trip. But I would never travel second class, which is irritatingly ambiguous. I don't like the appearances of people traveling in a second class coach.

Uchida then goes on to consider how he might get the necessary money to travel first class from Tokyo to Osaka and back. Finally, he goes to see one of his friends.

"I would like to go to Osaka."

"Ah, that is a good idea."

"So I came to see you on this matter."

"Is it an urgent business?"

"No. I don't have any particular reason, but I think I will go any way."

"Are you going to stay there for some time?"

"No. I think I will return immediately. Depending on the circumstances, I might even come back on the night train as soon as I arrive at Osaka."

"What do you mean depending on the circumstances?"

"Depending on how much travel money I have. If I have sufficient money, I will come back immediately. If I don't have enough, I might stay in Osaka for one night."

"I don't quite understand you."

"On the contrary, everything is clear. I have considered the matter with great care."

"Is that so?"

"Anyway, can you lend me some money?"

The idiot train essays are full of irrelevant and self-conscious prose writings of the finest quality. It is impossible to convey all the subtle nuances embedded in the original Japanese text, but something is better than nothing.

Uchida's dry and witty wisdom teaches us that that life is not about some kind of dreamed-of achievements, but that rather the process of living along ultimately justifies itself.

Uchida is a disciple of the great novelist Soseki Natsume.

Humorist, novelist, essayist Hyakken Uchida

Related URL

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natsume_Soseki

http://www.jlpp.jp/e_st05_uchida_h.html

In the opening sentence of the first volume of the Idiot Train, Uchida confesses thus (translation from Japanese mine)

I call this trip idiot train because people would say so behind my back anyway. Needless to say, I myself do not consider this undertaking to be that of an idiot. To be honest, you don't need a reason to go somewhere. I don't have any reason in particular to do so, but I have made up my mind to go to Osaka on the train.

As I do not have any particular reason to make this trip, it is ridiculous to travel second or third class. Traveling first class is always the best. At the age of 50, I made up my mind to always travel first class. In spite of my determination, I might be obliged to travel third class when I have no money and yet have some specific reason to make the trip. But I would never travel second class, which is irritatingly ambiguous. I don't like the appearances of people traveling in a second class coach.

Uchida then goes on to consider how he might get the necessary money to travel first class from Tokyo to Osaka and back. Finally, he goes to see one of his friends.

"I would like to go to Osaka."

"Ah, that is a good idea."

"So I came to see you on this matter."

"Is it an urgent business?"

"No. I don't have any particular reason, but I think I will go any way."

"Are you going to stay there for some time?"

"No. I think I will return immediately. Depending on the circumstances, I might even come back on the night train as soon as I arrive at Osaka."

"What do you mean depending on the circumstances?"

"Depending on how much travel money I have. If I have sufficient money, I will come back immediately. If I don't have enough, I might stay in Osaka for one night."

"I don't quite understand you."

"On the contrary, everything is clear. I have considered the matter with great care."

"Is that so?"

"Anyway, can you lend me some money?"

The idiot train essays are full of irrelevant and self-conscious prose writings of the finest quality. It is impossible to convey all the subtle nuances embedded in the original Japanese text, but something is better than nothing.

Uchida's dry and witty wisdom teaches us that that life is not about some kind of dreamed-of achievements, but that rather the process of living along ultimately justifies itself.

Uchida is a disciple of the great novelist Soseki Natsume.

Humorist, novelist, essayist Hyakken Uchida

Related URL

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natsume_Soseki

http://www.jlpp.jp/e_st05_uchida_h.html

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Reflections on the ever-changing

The past is a vast stage for metamorphoses. The critic Hideo Kobayashi once remarked to Yasunari Kawabata, the author of "Snow Country".

"Not much can be expected out of a living human. What a man thinks, says, and does, is never reliably predictable, whether you speak of yourself or of others. It is next to impossible to make a living human the object of your appreciation or serious observation. On the other hand, the dead are quite admirable. Why is it that the impression and the whole character of a man become quite clear, once he is dead? It is quite probable that dead men are the only true human beings that we come to know in this world. Are we living humans only animals who gradually become true humans as we approach our mortal end?"

(Excerpt from "Reflections on the ever-changing", original Japanese text published in 1941. Translation mine)

What Kobayashi speaks of men here has a universal relevance. The past is never fixed, and the significance of a particular experience becomes clear only after some time has passed since its occurrence. Maturation requires the workings of time. A child is never a child as it happens. You can appreciate your own childhood in the true sense only after you become an adult, when you reflect on what happened so long ago.

One's past is a rich fountain of significant experience, just as the future is an arena for unpredictability. Only in the long-gone past can one find solace and the food for soul. With a will to recall and a freedom of imagination, the past becomes a realm of vivid close-to-heart.

Hideo Kobayashi (1902-1983)

"Not much can be expected out of a living human. What a man thinks, says, and does, is never reliably predictable, whether you speak of yourself or of others. It is next to impossible to make a living human the object of your appreciation or serious observation. On the other hand, the dead are quite admirable. Why is it that the impression and the whole character of a man become quite clear, once he is dead? It is quite probable that dead men are the only true human beings that we come to know in this world. Are we living humans only animals who gradually become true humans as we approach our mortal end?"

(Excerpt from "Reflections on the ever-changing", original Japanese text published in 1941. Translation mine)

What Kobayashi speaks of men here has a universal relevance. The past is never fixed, and the significance of a particular experience becomes clear only after some time has passed since its occurrence. Maturation requires the workings of time. A child is never a child as it happens. You can appreciate your own childhood in the true sense only after you become an adult, when you reflect on what happened so long ago.

One's past is a rich fountain of significant experience, just as the future is an arena for unpredictability. Only in the long-gone past can one find solace and the food for soul. With a will to recall and a freedom of imagination, the past becomes a realm of vivid close-to-heart.

Hideo Kobayashi (1902-1983)

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

White magic

Most of Wolfgang Amdeus Mozart's music are in major keys. His music represents optimism and belief in beauty and good. In an impressive moment in Die Zauberflote, Monostatos and the gang try to capture Papageno and Pamina. At the sound of the magic bell, they all begin to dance, singing Das klinget so herrlich, das klinget so schön! It is absurd, and is so movingly beautiful. Needless to say, Mozart as a man of the world must have known that human societies are not so simple as that villains forget their vicious wills and surrender to the power of beauty so easily. However, as a musical fantasy it is of the purest quality, and is tinged with sadness.

Around the time of his mother's death in Paris, Mozart composed the 31st Symphony ("Paris"). Although personally a time of anxiety and sadness, the symphony does not reveal any sign of negative emotions. The music is full of youthful joy, oblivious of life's woes and sadness.

Mozart's compositions are excellent examples of what I metaphorically call "white magic", an act of good will to bring about beauty and love into the world. It is an interesting fact that white magic in this sense derives its energy in part from negative emotions. An enigma of human psyche is that negative emotions can be turned into positive emotions somehow. This "alchemy of mind" is evident in some of the masters of expressive art, notably Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Johann Wolfgang Goethe.

The determination to use only "white magic" in one's life is a worth one. It is malicious for the self, not to mention for the society, to give a straight expression of one's negative emotions. "Black magic" brings only misfortunes and tragedy into the world. It is worth conscious and unconscious efforts to try to turn one's negative emotions into positive ones, to use only "white magic". It is possible to do so. Just Listen to Mozart's music and be touched.

Mozart the "white magician"

Around the time of his mother's death in Paris, Mozart composed the 31st Symphony ("Paris"). Although personally a time of anxiety and sadness, the symphony does not reveal any sign of negative emotions. The music is full of youthful joy, oblivious of life's woes and sadness.

Mozart's compositions are excellent examples of what I metaphorically call "white magic", an act of good will to bring about beauty and love into the world. It is an interesting fact that white magic in this sense derives its energy in part from negative emotions. An enigma of human psyche is that negative emotions can be turned into positive emotions somehow. This "alchemy of mind" is evident in some of the masters of expressive art, notably Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Johann Wolfgang Goethe.

The determination to use only "white magic" in one's life is a worth one. It is malicious for the self, not to mention for the society, to give a straight expression of one's negative emotions. "Black magic" brings only misfortunes and tragedy into the world. It is worth conscious and unconscious efforts to try to turn one's negative emotions into positive ones, to use only "white magic". It is possible to do so. Just Listen to Mozart's music and be touched.

Mozart the "white magician"

Monday, December 25, 2006

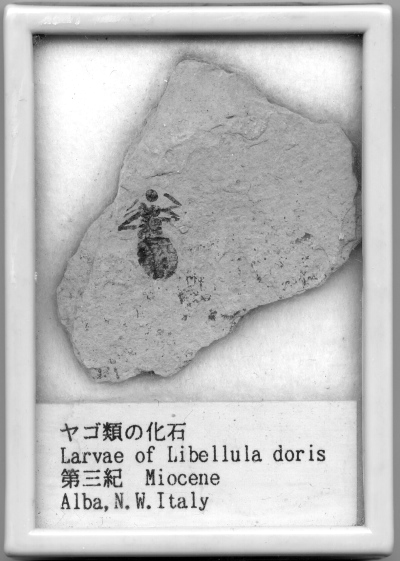

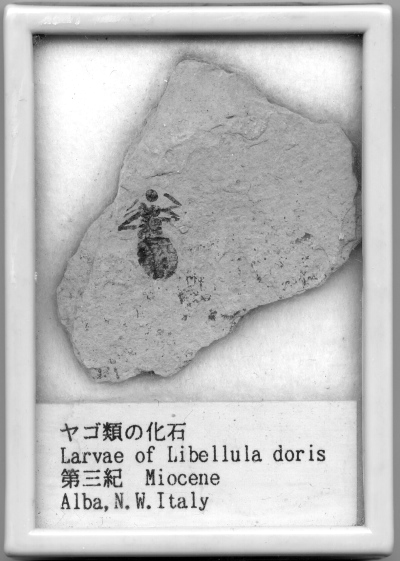

Found art.

Marcel Duchamp's "readymade" is different from conceptual art. When Duchamp signed "R. Mutt" on a urinal to turn it into a piece of art, it was not that any urinal would do. It must have been that particular urinal, with that particular shape and color.

The alternative term, "found art", should indicate a careful aesthetic search process to be a significant description of what is going on. Otherwise it loses legitimacy as a methodology of art.

For example, when a stone is used in a "found art" piece, it should not be any stone, just representing the concept of it. If you are given the instruction to "express yourself" with a stone, you could keep searching for years on end, without discovering the stone that just fits your sensitivity and intentionality. Uncovering a good found art object can be a very serious undertaking indeed.

The serendipitous discovery of a good "readymade" or "found art" object tests the artist's aesthetic senses, just as in the "created" pieces in the traditional sense. This is a worth remembering point when discussing this particular category of art.

Some part of the sense of bewilderment and wayward value the term "ready made" or "found art" conjectures in one's mind, however, might actually originate in the gray zone between illegitimacy and recognition. Refinement should not lead to an overkill of the original stigma.

My own favorite "found art" is the fossil of a nymph of a dragon fly. I discovered it in a fossil shop in the Kinokuniya bookstore in Tokyo. The shape is indicative of a fighting spirit. It is one of my treasured possessions.

I have not "signed" this readymade object yet, though.

The alternative term, "found art", should indicate a careful aesthetic search process to be a significant description of what is going on. Otherwise it loses legitimacy as a methodology of art.

For example, when a stone is used in a "found art" piece, it should not be any stone, just representing the concept of it. If you are given the instruction to "express yourself" with a stone, you could keep searching for years on end, without discovering the stone that just fits your sensitivity and intentionality. Uncovering a good found art object can be a very serious undertaking indeed.

The serendipitous discovery of a good "readymade" or "found art" object tests the artist's aesthetic senses, just as in the "created" pieces in the traditional sense. This is a worth remembering point when discussing this particular category of art.

Some part of the sense of bewilderment and wayward value the term "ready made" or "found art" conjectures in one's mind, however, might actually originate in the gray zone between illegitimacy and recognition. Refinement should not lead to an overkill of the original stigma.

My own favorite "found art" is the fossil of a nymph of a dragon fly. I discovered it in a fossil shop in the Kinokuniya bookstore in Tokyo. The shape is indicative of a fighting spirit. It is one of my treasured possessions.

I have not "signed" this readymade object yet, though.

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Menuhin's Messiah

As Christmas approaches, I am fond of playing George Frideric Handel's Messiah while at work on a CD or DVD. I especially love the part on the last judgment.

At the senior high school in Tokyo, I had several good friends, with whom I would discuss literature and music and other things that would interest a "highbrow" teenager growing up in the capital. One day, I was discussing Handel with one of my most respected friends then and ever since, Akira Wani, now a professor of law at the University of Tokyo. Akira mentioned that he usually prefer German to English in a classical oral music. However, he said, Handel's Messiah was a rare exception. He definitely preferred hearing Messiah in English to ditto in German, namely the arrangement and translation by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

One of my cherished memories of classic music concerts concerns the time when I heard Messiah in the Royal Albert Hall in London. The conductor was Yehudi Menuhin. The timing is a little obscure, but it must have been the winter of 1996 to 1997, only a few years before Menuhin's death in 1999.

It was the first time I heard Messiah in a concert hall, and I was amused to see the audience stand up just before the "Hallelujah" chorus, in a tradition allegedly started by King George II, who was so moved by the music.

On that day, the moment of truth came at the very beginning, even before a single note was played. The audiences were seated, and the orchestra was finished with the tuning. Menuhin came to the podium, showered with an enthusiastic applause, and gently raised his hand to conduct. He was about to move the baton downwards, when there was a slight rustle in the auditorium. Menuhin stopped the baton just in time, and without moving his raised hand, turned his head to see a late audience made his way to the seat.

There I saw, still vivid in my memory, the great violist and conductor holding his action like a living statue, literary motionless, waiting for the late comer to be seated.

When the unfortunate violator finally found his seat, Menuhin moved down his baton, and the music started, as nothing had happened. A good part of a minute must have passed during the incident. All the while, it was as if conducting time was just held from proceeding until the nuisance was removed, and that was just that.

I sometimes remember Menuhin in that posture when I listen to Messiah. It is the image of a mature and inspiring spirituality encapsulated in a human flesh, revealed at the time of an embarrassment.

At the senior high school in Tokyo, I had several good friends, with whom I would discuss literature and music and other things that would interest a "highbrow" teenager growing up in the capital. One day, I was discussing Handel with one of my most respected friends then and ever since, Akira Wani, now a professor of law at the University of Tokyo. Akira mentioned that he usually prefer German to English in a classical oral music. However, he said, Handel's Messiah was a rare exception. He definitely preferred hearing Messiah in English to ditto in German, namely the arrangement and translation by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

One of my cherished memories of classic music concerts concerns the time when I heard Messiah in the Royal Albert Hall in London. The conductor was Yehudi Menuhin. The timing is a little obscure, but it must have been the winter of 1996 to 1997, only a few years before Menuhin's death in 1999.

It was the first time I heard Messiah in a concert hall, and I was amused to see the audience stand up just before the "Hallelujah" chorus, in a tradition allegedly started by King George II, who was so moved by the music.

On that day, the moment of truth came at the very beginning, even before a single note was played. The audiences were seated, and the orchestra was finished with the tuning. Menuhin came to the podium, showered with an enthusiastic applause, and gently raised his hand to conduct. He was about to move the baton downwards, when there was a slight rustle in the auditorium. Menuhin stopped the baton just in time, and without moving his raised hand, turned his head to see a late audience made his way to the seat.

There I saw, still vivid in my memory, the great violist and conductor holding his action like a living statue, literary motionless, waiting for the late comer to be seated.

When the unfortunate violator finally found his seat, Menuhin moved down his baton, and the music started, as nothing had happened. A good part of a minute must have passed during the incident. All the while, it was as if conducting time was just held from proceeding until the nuisance was removed, and that was just that.

I sometimes remember Menuhin in that posture when I listen to Messiah. It is the image of a mature and inspiring spirituality encapsulated in a human flesh, revealed at the time of an embarrassment.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Magnets and the car park

As a child, I wanted to become a scientist, nothing else. The image of two mad-haired men standing in front of the blackboard, scribing equations all over the place, for hours and hours on end, has stayed as an icon of insanely great fun and excellence throughout my childhood. I did very well at school, and teachers advised me to become a medical doctor or a lawyer, but these career possibilities never touched my heart as an actual life's option, until much later into adulthood.

The beginning was a bit strange. I was collecting butterflies as a kid. Then, at the age of 8, magnets suddenly captured my imagination. As I walked to school, I would wonder why it was that magnets attracted metals and sticked to each other in the specific way. I still remember how at one period I went on thinking about the mystery of the magnet for about a month, every morning and afternoon, as I meandered through the small streets of the rural town I was living in at that time.

There was this particular car park, where the sun shone on the ground and you got a shimmering and white impression. As I passed by it, there was something about the scene that made me think of the magnets in a deep manner. The small child that I was associated the car park with the enigma of magnets. To this day, I don't know why.

It is impossible to go back and verify in person, as the car park is long gone.

The beginning was a bit strange. I was collecting butterflies as a kid. Then, at the age of 8, magnets suddenly captured my imagination. As I walked to school, I would wonder why it was that magnets attracted metals and sticked to each other in the specific way. I still remember how at one period I went on thinking about the mystery of the magnet for about a month, every morning and afternoon, as I meandered through the small streets of the rural town I was living in at that time.

There was this particular car park, where the sun shone on the ground and you got a shimmering and white impression. As I passed by it, there was something about the scene that made me think of the magnets in a deep manner. The small child that I was associated the car park with the enigma of magnets. To this day, I don't know why.

It is impossible to go back and verify in person, as the car park is long gone.

Friday, December 22, 2006

Waley's translation of Genji

The Tale of Genji is a Japanese classic written by a noble woman (Lady Murasaki) at the beginning of the 11th century. Acclaimed as a masterpiece full of sensitivities towards the subtle and intricate ups and downs in the love and suffering of the mortal human being, it is the most highly regarded novel of all time. However, the language is not easily accessible. Without a devoted and long learning, the modern Japanese cannot hope to appreciate the original text of Genji.

As a result, translations into modern Japanese have been attempted several times, including those by famous writers and poets, notably by Junichiro Tanizaki and Akiko Yosano. It is through modern translations that the majority of Japanese get to know Genji.

In a famous anecdote, literary critic Hideo Kobayashi was discussing Genji with the writer Hakucho Masamune. Masamune mentioned that he recently came to appreciate the beauty of Genji. Koabayashi asked him if he was reading Tanizaki or Yosano. Masamune answered "no, I am actually reading the translation by Arthur Waley". In his days, Kobayashi was fond of telling this particular anectodate, as it was felt to be a bit awkward and funny that a domestic writer should get to know the essence of the great novel through a foreign translation.

Waley's translation is beautiful. I am fond of it myself. It is deeply moving. Wet and sentimental expression, normally hard to find in the English language, gives the reader's heart wobbles and waverings. It is as if a moist and poignant wind has blown into a crisp and critical landscape. The marriage of the sentimental novel and the more or less practical language has resulted in an unforgettable masterpiece.

Getting to know the essence of a work in your native tongue through a foreign translation is a wonderful demonstration of interdependency of the cultural development in various parts of the globe.

As a result, translations into modern Japanese have been attempted several times, including those by famous writers and poets, notably by Junichiro Tanizaki and Akiko Yosano. It is through modern translations that the majority of Japanese get to know Genji.

In a famous anecdote, literary critic Hideo Kobayashi was discussing Genji with the writer Hakucho Masamune. Masamune mentioned that he recently came to appreciate the beauty of Genji. Koabayashi asked him if he was reading Tanizaki or Yosano. Masamune answered "no, I am actually reading the translation by Arthur Waley". In his days, Kobayashi was fond of telling this particular anectodate, as it was felt to be a bit awkward and funny that a domestic writer should get to know the essence of the great novel through a foreign translation.

Waley's translation is beautiful. I am fond of it myself. It is deeply moving. Wet and sentimental expression, normally hard to find in the English language, gives the reader's heart wobbles and waverings. It is as if a moist and poignant wind has blown into a crisp and critical landscape. The marriage of the sentimental novel and the more or less practical language has resulted in an unforgettable masterpiece.

Getting to know the essence of a work in your native tongue through a foreign translation is a wonderful demonstration of interdependency of the cultural development in various parts of the globe.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Unremembered memories.

People usually think that the whole point of memory, especially that of episodes, is in the fact that it can be explicitly recalled. Unremembered memories seems to be a contradiction in definition, or at least useless. However, it is a fact that unremembered memories are important ingredients of our life, something we cannot really do without.

Think of, for example, what explicit memories you have from your childhood, in relation to your parents. You have spent endless hours of life with your mother and father, and yet, it is not easy to explicitly remember specific incidents and occurrences, especially as you go back in life to your infancy. The sentiment towards your parents, the idea of "mother" or "father" that is conjured up within you when thinking of them, is genuinely a product of these unremembered memories. The fact that you cannot "remember" all these episodes from the time you spent with your parents does not mean that in the brain there isn't this rich layer of records of your life under the care of well meaning adults in a past now so distant.

I had a striking personal experience concerning the significance of unremembered memories myself. For a while, I heard repeatedly the name "Shigeo Miki", an anatomist who taught at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. People spoke of Miki with reverence, and I was very much interested in his idea that during fetal development the history of the evolution of live is virtually repeated. Miki's idea about "life memory" had a strong influence on many people. The eloquence of his lectures was a live and growing legend.

I, however, was under the impression that I had never been blessed by his speech or his writings. I somehow had not read any of his books, and when people spoke of Miki, it was felt as if he was somebody in the distance, glowing with intellect and wisdom but thus far not having much to do with my own life. And I felt it was too late. He had long passed away.

Then one day, I realized with a shock that I actually attended one of his lectures once. I was still early 20 something, studying Physics as an undergraduate in University of Tokyo. I was walking in the campus with my girl friend, and we accidentally noticed a poster depicting a human fetus. We were greatly interested and walked straight into the lecture room.

The room was packed with people, there were not seats available, and we stood at the very back of the auditorium. The light went out and we were enclosed in gentle darkness. The speaker showed a series of photos of the fetus in development, and discussed how the whole history of life's evolution is repeated in the organic development that kick-starts every one of our own lives.

I do not explicitly recall the details of his speech, but I faintly remember that I was very moved. When the talk was over, there was a thunder of applause.

My girl friend had been standing beside me during the lecture. When the light came back, I realized that the left part of my jacket was wet. I took a look and realized that it was the tears of my girlfriend, who had buried her face in my breast.

We went out of the lecture room into the fresh air of late spring. As we walked, I asked my girl friend what made her cry. She answered that the lecture convinced her that human life is very valuable. She then added.

"Yet, we continue to kill each other in the war. Why?".

That was then. Almost 20 years passed, my girl friend's and my own life went into different trajectories, and I somehow did not recall the incident for a long time. Then one day, I suddenly remembered the lecture on that day and realized that it must have been given by Shigeo Miki himself. I was strangely convinced the moment I remembered it.

I went around checking. I asked the art critic Hideto Fuse, who was a disciple of Miki whether Miki ever gave a lecture in University of Tokyo. Hideto answered yes. Miki talked twice. It appeared that I attended the second lecture, the last lecture Miki gave in University of Tokyo, before his death a few years later.

The whole episode shook my world view from the deep root. All these years during which I was not aware that I had attended Miki's lecture once, I was without knowing under the influence of his thoughts. Once, as I was watching the waves on a beach in the island of Bali, Indonesia, I was thinking of the long history of life forms as they evolved in the sea and slowly made it to the land. I was contemplating the significance of our own existence, and I thought I was doing it on my own. Actually, my whole thoughts were under the influence of Shigeo Miki, unaware of it though I was.

Thus, memories that are not explicitly recalled play an important role in life. Our spiritual life is made of unremembered memories.

Think of, for example, what explicit memories you have from your childhood, in relation to your parents. You have spent endless hours of life with your mother and father, and yet, it is not easy to explicitly remember specific incidents and occurrences, especially as you go back in life to your infancy. The sentiment towards your parents, the idea of "mother" or "father" that is conjured up within you when thinking of them, is genuinely a product of these unremembered memories. The fact that you cannot "remember" all these episodes from the time you spent with your parents does not mean that in the brain there isn't this rich layer of records of your life under the care of well meaning adults in a past now so distant.

I had a striking personal experience concerning the significance of unremembered memories myself. For a while, I heard repeatedly the name "Shigeo Miki", an anatomist who taught at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. People spoke of Miki with reverence, and I was very much interested in his idea that during fetal development the history of the evolution of live is virtually repeated. Miki's idea about "life memory" had a strong influence on many people. The eloquence of his lectures was a live and growing legend.

I, however, was under the impression that I had never been blessed by his speech or his writings. I somehow had not read any of his books, and when people spoke of Miki, it was felt as if he was somebody in the distance, glowing with intellect and wisdom but thus far not having much to do with my own life. And I felt it was too late. He had long passed away.

Then one day, I realized with a shock that I actually attended one of his lectures once. I was still early 20 something, studying Physics as an undergraduate in University of Tokyo. I was walking in the campus with my girl friend, and we accidentally noticed a poster depicting a human fetus. We were greatly interested and walked straight into the lecture room.

The room was packed with people, there were not seats available, and we stood at the very back of the auditorium. The light went out and we were enclosed in gentle darkness. The speaker showed a series of photos of the fetus in development, and discussed how the whole history of life's evolution is repeated in the organic development that kick-starts every one of our own lives.

I do not explicitly recall the details of his speech, but I faintly remember that I was very moved. When the talk was over, there was a thunder of applause.

My girl friend had been standing beside me during the lecture. When the light came back, I realized that the left part of my jacket was wet. I took a look and realized that it was the tears of my girlfriend, who had buried her face in my breast.

We went out of the lecture room into the fresh air of late spring. As we walked, I asked my girl friend what made her cry. She answered that the lecture convinced her that human life is very valuable. She then added.

"Yet, we continue to kill each other in the war. Why?".

That was then. Almost 20 years passed, my girl friend's and my own life went into different trajectories, and I somehow did not recall the incident for a long time. Then one day, I suddenly remembered the lecture on that day and realized that it must have been given by Shigeo Miki himself. I was strangely convinced the moment I remembered it.

I went around checking. I asked the art critic Hideto Fuse, who was a disciple of Miki whether Miki ever gave a lecture in University of Tokyo. Hideto answered yes. Miki talked twice. It appeared that I attended the second lecture, the last lecture Miki gave in University of Tokyo, before his death a few years later.

The whole episode shook my world view from the deep root. All these years during which I was not aware that I had attended Miki's lecture once, I was without knowing under the influence of his thoughts. Once, as I was watching the waves on a beach in the island of Bali, Indonesia, I was thinking of the long history of life forms as they evolved in the sea and slowly made it to the land. I was contemplating the significance of our own existence, and I thought I was doing it on my own. Actually, my whole thoughts were under the influence of Shigeo Miki, unaware of it though I was.

Thus, memories that are not explicitly recalled play an important role in life. Our spiritual life is made of unremembered memories.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Long life

With long life comes the merit of maturity. The brain never stops learning. The way the neural circuits are updated is very sustainable and open-ended. So it pays to aspire to live on.

Gautama Buddha came to "great enlightenment" at the age of 35. History tells that there was a prolonged aftermath of the momentous event. He went on to live until the age of 80.

Coming to an intimate understanding of the mystery of the universe, the ultimate cause of the suffering of humans and all living things, seems to be so final that it feels strange to go on living after the climax. Even if Buddha's life after the enlightenment was an anticlimax, there should have been many poignant points through the course, as he went on to breathe and communicate and expose himself to the imperfect occurrences on the earth.

It is not difficult to imagine there must have been ups and downs. Earthly events seems to be strange to follow the great enlightenment. The truth lies in that strangeness.

The greatest blessing of long life might actually be in that sweet strangeness of the gradual ailment and deterioration and alienation from the earthly joys of living.

Gautama Buddha came to "great enlightenment" at the age of 35. History tells that there was a prolonged aftermath of the momentous event. He went on to live until the age of 80.

Coming to an intimate understanding of the mystery of the universe, the ultimate cause of the suffering of humans and all living things, seems to be so final that it feels strange to go on living after the climax. Even if Buddha's life after the enlightenment was an anticlimax, there should have been many poignant points through the course, as he went on to breathe and communicate and expose himself to the imperfect occurrences on the earth.

It is not difficult to imagine there must have been ups and downs. Earthly events seems to be strange to follow the great enlightenment. The truth lies in that strangeness.

The greatest blessing of long life might actually be in that sweet strangeness of the gradual ailment and deterioration and alienation from the earthly joys of living.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Does Santa exit?

At the end of the year 2001, I found myself in Haneda airport which serves the metropolitan Tokyo. I just came back on an early morning flight from a southbound trip, and was eating curry and rice in a passenger restaurant. There was a family seated next to my table. A girl, about 5 years of age, was chatting with her smaller sister.

"Hey, do you think Santa Claus exists? What do you think?"

Then, the little girl went on to state her opinion.

"Well, I think in this way......"

I could not hear what she went on to say, as a sudden surge of emotion overwhelmed me. I put down my spoon on the plate.

"Does Santa Claus exist?"

It struck me that that was the most important question that a girl, or indeed any adult, could ask of the world.

As it happened, seven years had passed since I came to realize the problem of qualia, the enigma of the relation between the mind and the brain.

The heart-throbbing reality with which Santa Claus emerges for a 5 year old girl has its origin in imagination. Santa Claus has its full reality only in the domain of the imagined. The proof of the existence of Santa does not rest on the physical appearance of a fat man with a white beard dressed in red.

A five year old girl knows fully well that Santa would never emerge as a physical reality in front of her eyes. Santa Claus is never "here" and "now". We never experience Santa in a vivid phenomenality as in the case of an apple on the table. In spite of the lack of physical existence, or rather, because of it, Santa Clause has an acute reality for the 5 year old girl and the rest of us.

(Opening sentences from "Brain and Imagination" (Nou to Kasou), by Kenichiro Mogi (2004), winner of the 4th Hideo Kobayashi prize. Translation from Japanese by the author himself).

"Hey, do you think Santa Claus exists? What do you think?"

Then, the little girl went on to state her opinion.

"Well, I think in this way......"

I could not hear what she went on to say, as a sudden surge of emotion overwhelmed me. I put down my spoon on the plate.

"Does Santa Claus exist?"

It struck me that that was the most important question that a girl, or indeed any adult, could ask of the world.

As it happened, seven years had passed since I came to realize the problem of qualia, the enigma of the relation between the mind and the brain.

The heart-throbbing reality with which Santa Claus emerges for a 5 year old girl has its origin in imagination. Santa Claus has its full reality only in the domain of the imagined. The proof of the existence of Santa does not rest on the physical appearance of a fat man with a white beard dressed in red.

A five year old girl knows fully well that Santa would never emerge as a physical reality in front of her eyes. Santa Claus is never "here" and "now". We never experience Santa in a vivid phenomenality as in the case of an apple on the table. In spite of the lack of physical existence, or rather, because of it, Santa Clause has an acute reality for the 5 year old girl and the rest of us.

(Opening sentences from "Brain and Imagination" (Nou to Kasou), by Kenichiro Mogi (2004), winner of the 4th Hideo Kobayashi prize. Translation from Japanese by the author himself).

Sunday, December 10, 2006

Something watery

I never thought of Tokyo as a beautiful city. Even the masterful touch of Ozu films such as "Tokyo Story" can barely turn it into a fantasy land of aesthetic joy. I love the city, though, because my life and work are in it, my friends, my beloved ones, and my past, present, and most probably the future. After all, I went to the university in Tokyo, have a bunch of graduate students working with me in the lab, commute a few times a week to the NHK broadcast center in Shibuya to host the "Professionals" chat show, and dine and dream on a daily basis.

When I came back from Kolkata a few weeks ago, I had a refreshing experience. In a nutshell, Tokyo never looked that beautiful. After the scenery I encountered in the Indian city, everything in Tokyo seemed to be glittering and smoothly plastic, a place ever throbbing with water-surface-wavering sensitivities. As I passed by the ANA hotel Tokyo near Roppongi, bound for a lecture and shoot session in T.V. Asahi, I could almost cry for the sheer joy of sensuality that the Tokyo night vision provides. It was a revelation that stayed with me ever since.

I am not saying that Kolkata was dirty compared to Tokyo. I am only stating that Tokyo has its unique features as regards its appearance, especially in reference to the texture of materials that make up the buildings. There's something watery--reflecting the abundant moisture of weather consisting of distinct four seasons--which became very apparent after the exposure to a contrasting climate in India.

I always thought that Tokyo lost its exquisite charm that it used to possess, captured in the great Ukiyoe woodprints in the Edo era. If there is still charm apart from being the "world-capital-of-otaku" in the capital city, I as a resident have got to find it, in the bustling noise of mobile phones and trains that operate on precision.

A Ukiyoe woodprint from the Edo era depicting Nihonbashi, or the "Bridge of Japan" in Tokyo.

When I came back from Kolkata a few weeks ago, I had a refreshing experience. In a nutshell, Tokyo never looked that beautiful. After the scenery I encountered in the Indian city, everything in Tokyo seemed to be glittering and smoothly plastic, a place ever throbbing with water-surface-wavering sensitivities. As I passed by the ANA hotel Tokyo near Roppongi, bound for a lecture and shoot session in T.V. Asahi, I could almost cry for the sheer joy of sensuality that the Tokyo night vision provides. It was a revelation that stayed with me ever since.

I am not saying that Kolkata was dirty compared to Tokyo. I am only stating that Tokyo has its unique features as regards its appearance, especially in reference to the texture of materials that make up the buildings. There's something watery--reflecting the abundant moisture of weather consisting of distinct four seasons--which became very apparent after the exposure to a contrasting climate in India.

I always thought that Tokyo lost its exquisite charm that it used to possess, captured in the great Ukiyoe woodprints in the Edo era. If there is still charm apart from being the "world-capital-of-otaku" in the capital city, I as a resident have got to find it, in the bustling noise of mobile phones and trains that operate on precision.

A Ukiyoe woodprint from the Edo era depicting Nihonbashi, or the "Bridge of Japan" in Tokyo.

Saturday, December 09, 2006

Dreaming of, but never actually reaching

My native tongue is Japanese. I started learning English at school when I was 12. I read the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy when I was at senior high. Gradually, I awakened to the universe of English, and have started to write, speak, and think in this language.

English is certainly useful. However, it is not the only medium of soul. When you come to realize that there are several thousand tongues on the globe, you are dazzled by the very fact and realize that you are truly living in the post-Babelian era. Even if you become well versed in several leading languages, you can never hope to come to appreciate the richness, subtlety, and the bliss of living in the respective cosmoses of the speech that cover the earth. A complex set of multiverses is a reality of life, not a purely theoretical construct.

The other day, I was in Atlanta, U.S.A, attending the society for neuroscience annual meeting. As I was leaving the city on a cab, bound for the airport, I was suddenly reminded of the fact that there are all these different climates on the earth. Autumn was deepening in Atlanta, the leaves turning into red and falling to the ground. In other parts of the globe at that very moment, however, monkeys would be hopping from bough to bough in a steamy jungle, icebergs persevering in the northerly wind, the sun scorching the desert, and the ocean slowly waving beneath a mellow spring sunbeam. All these diverse climates co-exist at the same time, embraced by the capacity of this chunk of rock that we call "the earth".

The multiverse of different languages and climates could not have possibly co-existed if the capacity of the earth was smaller. It is impossible to co-host the spectrum of climates in an artificial dome, however large. The earth capacity is a blessing and curse at the same time, the curse being that we cannot hope to see all that goes on in the world as we know it, making it impossible to actually construct a "panopticon" (Jeremy Bentham).

The limits of experiencing all that be is a noteworthy fact in the era of the small world network, where people can easily have the illusion of being able to connect to and experience all that goes on. We mortal souls are encapsulated evermore in the respective specimens of flesh, dreaming of, but never actually reaching, the dazzling totality of the life's experience on earth.

English is certainly useful. However, it is not the only medium of soul. When you come to realize that there are several thousand tongues on the globe, you are dazzled by the very fact and realize that you are truly living in the post-Babelian era. Even if you become well versed in several leading languages, you can never hope to come to appreciate the richness, subtlety, and the bliss of living in the respective cosmoses of the speech that cover the earth. A complex set of multiverses is a reality of life, not a purely theoretical construct.

The other day, I was in Atlanta, U.S.A, attending the society for neuroscience annual meeting. As I was leaving the city on a cab, bound for the airport, I was suddenly reminded of the fact that there are all these different climates on the earth. Autumn was deepening in Atlanta, the leaves turning into red and falling to the ground. In other parts of the globe at that very moment, however, monkeys would be hopping from bough to bough in a steamy jungle, icebergs persevering in the northerly wind, the sun scorching the desert, and the ocean slowly waving beneath a mellow spring sunbeam. All these diverse climates co-exist at the same time, embraced by the capacity of this chunk of rock that we call "the earth".

The multiverse of different languages and climates could not have possibly co-existed if the capacity of the earth was smaller. It is impossible to co-host the spectrum of climates in an artificial dome, however large. The earth capacity is a blessing and curse at the same time, the curse being that we cannot hope to see all that goes on in the world as we know it, making it impossible to actually construct a "panopticon" (Jeremy Bentham).

The limits of experiencing all that be is a noteworthy fact in the era of the small world network, where people can easily have the illusion of being able to connect to and experience all that goes on. We mortal souls are encapsulated evermore in the respective specimens of flesh, dreaming of, but never actually reaching, the dazzling totality of the life's experience on earth.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Qualia and Contingency

Lecture Records

"Qualia and Contingency"

Ken Mogi

Sony Computer Science Laboratories & Tokyo Institute of Technology

Talk given at

Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics

Kolkata, India

22nd November 2006

audio file(MP3, 44.9MB, 50 minutes)

"Qualia and Contingency"

Ken Mogi

Sony Computer Science Laboratories & Tokyo Institute of Technology

Talk given at

Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics

Kolkata, India

22nd November 2006

audio file(MP3, 44.9MB, 50 minutes)

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

To do everything you can

Google has been one of the great things that happened in our life. That's probably every person's fair assessment. Why it is so, however, merits examination.

It is true that google is using good old fashioned artificial intelligence. It was more or less agreed upon in the 1980s that computer algorithms and programs are not sufficient to reproduce something akin to human intelligence. People argued that perhaps we need "embodiment" to realize human intelligence, turning to robotics research, making robots play soccer. So it was in the air that good old fashioned A.I. was something "passé", not meriting further attention.

Then google came into the picture. It made use of the mundane old technology, but it did not stop at midpoint, it went on and on to do everything it could. As a result, it has grown into one of the most useful tools on the internet today.

It is an important intellectual rite of passage to realize that what computer networks can do at today is a far cry from what the human brain can achieve. It is a fallacy to assume that the internet can evolve to have something similar to human intelligence, let alone consciousness. On the other hand, these difficulties in principle should not stop us from doing everything we can today. There are infinitely many possibilities still to be explored and actualized, even in the mundane old technology of algorithms and programs.

Google taught us the power of the mundane, if it is tried real hard.

It is true that google is using good old fashioned artificial intelligence. It was more or less agreed upon in the 1980s that computer algorithms and programs are not sufficient to reproduce something akin to human intelligence. People argued that perhaps we need "embodiment" to realize human intelligence, turning to robotics research, making robots play soccer. So it was in the air that good old fashioned A.I. was something "passé", not meriting further attention.

Then google came into the picture. It made use of the mundane old technology, but it did not stop at midpoint, it went on and on to do everything it could. As a result, it has grown into one of the most useful tools on the internet today.

It is an important intellectual rite of passage to realize that what computer networks can do at today is a far cry from what the human brain can achieve. It is a fallacy to assume that the internet can evolve to have something similar to human intelligence, let alone consciousness. On the other hand, these difficulties in principle should not stop us from doing everything we can today. There are infinitely many possibilities still to be explored and actualized, even in the mundane old technology of algorithms and programs.

Google taught us the power of the mundane, if it is tried real hard.

The Professional Way

"The Professional Way" (the same URL translated into English by the google engine) is a weekly T.V. program broadcast by NHK, Japan's national television. It is a chat show where various "professionals" are invited from miscellaneous walks of life, revealing the secrets of their success and their continued commitment to better the already best. I have been hosting this show since January 2006.

I sometimes wonder what kind of a person I am. I am doing brain science at a corporate lab (Sony Computer Science Laboratories), have a lab in a University (Tokyo Institute of Technology), have written many books, write essays in magazines, have won a literary prize, and am hosting a chat show on T.V.

The other day I had the realization that I am perhaps a "hopeful monster", an anomaly seen from the regular stream, with many strange features, perhaps on the fringe right now, but hoping to be recognized as a genre of its own some day.

I sometimes wonder what kind of a person I am. I am doing brain science at a corporate lab (Sony Computer Science Laboratories), have a lab in a University (Tokyo Institute of Technology), have written many books, write essays in magazines, have won a literary prize, and am hosting a chat show on T.V.

The other day I had the realization that I am perhaps a "hopeful monster", an anomaly seen from the regular stream, with many strange features, perhaps on the fringe right now, but hoping to be recognized as a genre of its own some day.

Friday, June 30, 2006

My blog in Japanese

I keep my blog in Japanese more frequently than this one. The Japanese blog is fairly popular, with > 5000 visitors every day. Here's your chance to see what's going on in my life in more details. The translated version of my "Qualia Nikki" (qualia diary) "Qualia Nikki" (qualia diary).

The results of translation is very clumsy and reads like a mad man's scribbing (maybe it really is!).

The results of translation is very clumsy and reads like a mad man's scribbing (maybe it really is!).

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

The origin of consciousness

Here I annouce a new blog titled

"The origin of consciousness"

http://origin-of-consciousness.blogspot.com/

The first entry is

Origin of consciousness: the missing principles.

"The origin of consciousness"

http://origin-of-consciousness.blogspot.com/

The first entry is

Origin of consciousness: the missing principles.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)